On Tuesday, the Miami-Dade Housing Committee approved a redevelopment project aimed at transforming Miami’s Little Haiti and Little River neighborhoods, injecting an estimated $2.6 billion over the next decade to add thousands of apartments, retail spaces and transit upgrades. Spearheaded by the Coconut Grove-based Swerdlow Group, the final development agreement will now go before the Board of County Commissioners for final approval.

Collaborating with real estate company AJ Capital Partners, Swerdlow Group was the only developer to submit a proposal in response to Miami-Dade County’s bid to rebuild and expand four public housing projects.

Several residents and construction workers attended the March 11 meeting, calling on the developer to include community enhancements within its proposal. They urged committee members to demand worker protections, responsible contractors, and housing rates that are reasonably affordable.

The new development would include a mix of market rate, affordable and workforce units.

Commissioner Marleine Bastien, chair of the Housing Committee, and Commissioner Eileen Higgins had pulled the item for discussion to make way for community input. Bastien later raised concerns about incorporating the community’s requests into the final development plan.

“How do we make sure that some of the requests made today are included in the final community benefit package?” she asked.

Alex Ballina, director of Housing and Community Development, said his department would discuss the community’s requests with the developer. He also said there are community meetings scheduled to take place throughout the process, one of which already occurred last week.

Bastien urged Ballina and the developers to ensure those in attendance were invited to future gatherings.

“Make sure that you take their information and invite them,” she said.

The Plan

The Swerdlow Group’s proposal outlines the creation of a mixed-income, walkable community featuring approximately 7,500 residential units, including affordable, workforce, and market-rate housing. The breakdown includes 2,284 affordable units (aimed at those earning 60% of the area median income, or AMI), 1,398 workforce rental units (for those earning up to 120% AMI), and 2,048 workforce condos (subsidized for residents earning up to 140% AMI). AJ Capital is planning for the remaining 1,800 units to be priced at market or workforce rates.

The redevelopment would cover 65 acres, mostly financed privately, and is expected to span 10 years.

A brand new Tri-Rail station would be built at SG’s expense for an expected cost of $35.4 million.

The overall area, currently mostly industrial, would include key features such as big-box stores like Home Depot, 700,000 square feet of parks, and a pedestrian-friendly shopping street along Northwest 73rd Street. It would also include a new Tri-Rail station at SG’s expense, costing $35.4 million, which the county’s Transportation Planning Organization has approved as part of its 2050 Long Range Transportation Plan.

‘Build a Better Miami’

The development would include green spaces, retail stores and a pedestrian-friendly shopping street along Northwest 73rd Street.

Last week, anticipating Tuesday’s vote, the Build a Better Miami Coalition held a press conference demanding a developmentthat works for everyone. The coalition asked the Housing Committee for a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) that includes responsible subcontractors, heat protections for workers during construction, more affordable housing for residents with a yearly income below $90,000, living wages for new jobs, and a grant fund for local businesses to prevent displacement.

The Build a Better Miami Coalition is asking for a development that benefits all residents and workers.

Pastor Jacques St. Louis of Grace Evangelical Baptist Church urged elected officials to engage with the community.

“We’re not against progress; we just want it to be fair for all,” he said.

Pastor Jacques St. Louis of Grace Evangelical Baptist Church surrounded by individuals who form the Build a Better Miami Coalition.

The coalition also raised concerns about housing affordability, noting that while 60% of units will be reserved for workforce housing, only 40% will be designated for lower-income residents. Zaina Alsous, Miami director of We Count!, highlighted how many construction workers earn less than $40,000 annually.

“The prices being set are simply out of reach for most Miamians,” she said.

Medical students of the Dade County Street Response Team presented facts about construction workers and the dangers they face.

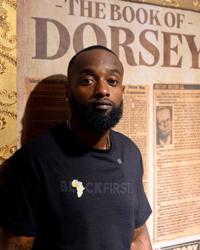

In response, Swerdlow Group included a CBA in itsproposal ensuring that 25% of new hires for subcontractors during construction will be low-income or public housing residents, and 30% of construction subcontracts will go to small, minority, or women-owned businesses. The plan also includes job preferences for local residents, particularly at Home Depot, and promises at least 3,840 construction jobs and 518 permanent ones. Moreover, the developer has committed to implementing heat protections in line with local, state, and federal workplace safety requirements, addressing some of the coalition’s demands.

Bastien commended Swerdlow for working with We Count! to ensure heat protection for workers.

“I hope you will continue to engage the community as you move forward with these developments to build more affordable housing,” she said.

Rising Property Values

Little Haiti has become one of South Florida's fastest-gentrifying neighborhoods, with longtime residents feeling increasingly alienated.

The project’s encompassing area has been known as Little Haiti since the 1980s, when Haitian refugees began moving into a neighborhood initially known as Little River. Little Haiti is one of the poorest neighborhoods in the county, with average households earning below $50,000 annually.

The economic burden faced by residents is exacerbated as home values in the neighborhood continue to soar, rising by about 19% since 2016. Many have grown wary of new development as a result.

Some fear the project will further raise property values, making the area unaffordable. Conversely, developers argue it will counter decades of disinvestment, suggesting that higher values could benefit longtime residents by allowing them to leverage their equity.

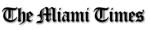

A map of Little Haiti and Little River shows the area where the developer plans to redevelop 65 acres of private and public land.

But community members like Ashley Toussaint, a lifelong Little Haiti resident and business owner, disagree. He describes how rising rents impacted his family's business, which transitioned from a brick-and-mortar office to a virtual one after rents tripled in just four years.

"There won’t be much availability for local business owners because they won’t have places to rent," he said.

Ashley Toussaint, a lifelong Little Haiti resident, business owner and member of Black Men Build, reflects on Little Haiti's changes over time.

During the Housing Committee’s meeting, Toussaint urged county commissioners and the developer to allocate at least $1 million to support longstanding small businesses displaced by construction.

Higgins requested the developer enhance community engagement and include protections for small businesses in the final plan.

Fears of Displacement

Little Haiti is considered one of the poorest neighborhoods in the county, with households earning below $50,000 annually.

Little Haiti has become one of South Florida'sfastest-gentrifying neighborhoods, with longtime residents feeling increasingly alienated. Toussaint describes the onset of gentrification as having taken place during the early 2000s, beginning with the displacement of Haitian residents from the Sabal Palm apartments.

"Now, many of your neighbors are not here anymore," he said. "I sometimes feel like a stranger in my own community."

Moe Simbert

Moe Simbert, a lead organizer with the Black Collective, shared similar concerns.

“It was a slow but killing process in Little Haiti because they took the heart out. It’s not just about beautifying the area; it’s about who gets to stay," Simbert said. "Haitian and Latinx immigrants, the people who built this community, are being pushed out because they can’t afford it anymore."

Simbert is cautious against promises made by developers, drawing parallels to previous redevelopment efforts like those in Liberty Square, where residents were promised they wouldn't be displaced but still faced difficulties.

A map shows the public housing properties to be redeveloped, including the Victory Homes public housing project.

Ericka Varela, a resident of Victory Homes, one of the public housing projects to be redeveloped, fears for the future.

“What worries me most about the relocation during the redevelopment is that we could be not allowed to return,” she said. “We deserve to leave with dignity, and the developer must take that into account and meet with all my neighbors.”

The developer has in turn promised no displacement. The project is being developed under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program, which ensures rents remain affordable, capped at 30% of a household's income.

“There will be no forced displacement of residents,” assured Michael Swerdlow, managing partner of SG Holdings.

Swerdlow Group also highlighted the broader economic benefits of the project, noting that the county stands to receive over $9.4 billion in revenue.